La decisione di assegnare al curatore belga Chris Dercon (Tate Modern Museum) la direzione artistica dello storico teatro di Berlino-Est “Volksbühne” ha generato molte controversie nell’ambiente teatrale tedesco. Dopo il lungo mandato di 25 anni del regista Frank Castorf, che aveva impresso alla struttura una forte identità artistica e mantenuto il suo profondo radicamento al territorio, il Volksbühne pare andare ora verso una maggiore “internazionalizzazione” fatta di produzioni estere in tour, una particolare attenzione alla danza e l’utilizzo di altri luoghi per la messa in scena oltre al palco del teatro (uno dei più grandi del mondo).

Ma per alcuni questo significa tradire lo spirito autentico del posto, che ha sempre unito la sua vocazione “popolare” e locale con la tensione verso l’avanguardia e la sperimentazione. Abbiamo parlato con Holger Syme, docente di teatro all’Università di Toronto, curatore del blog Dispositio, spettatore assiduo del Volksbühne e autore di “How to Kill a Great Theater: The Tragedy of Volksbühne“, articolo duramente critico nei confronti del “nuovo corso” che il teatro sta per intraprendere dalla prossima stagione.

Ci puoi esporre i motivi delle tue critiche alla decisione di nominare Chris Dercon come nuovo direttore del Volksbühne?

Innanzitutto penso sia doveroso fare un piccolo riassunto della storia di questo teatro. Il Volksbühne è una struttura attiva da più di cent’anni ed è sempre stato un punto di riferimento non solo per la scena tedesca ma direi per tutto l’ambiente teatrale internazionale, ponendosi spesso anche in una posizione di sfida nei confronti dello status quo politico. Durante gli anni venti, per esempio, sotto la direzione di Piscator ha influenzato fortemente Brecht, negli anni ‘70 ai tempi della DDR è stato uno dei pochi luoghi in cui si è generato un teatro controculturale, seppur per un lasso di tempo molto breve… poco dopo la caduta del Muro l’amministrazione della città di Berlino ha nominato per la guida del Volksbühne Frank Castorf, un regista all’epoca molto giovane e con una reputazione da “ribelle”. Si trattava di una scelta abbastanza sorprendente e lo stesso Castorf si dichiarò fortemente stupito della nomina ma era deciso ad agire in maniera radicale.

Sotto la sua direzione di ormai 25 anni, attraversando ovviamente anche fasi calanti, il Volksbühne si è posto come vera e propria incubatrice di sviluppo teatrale, un’esperienza seminale per la Germania e per l’intera Europa. È diventato un luogo dove molti registi internazionali venivano per trovare ispirazione e osservare nuove direzioni di ricerca. 25 anni sono in effetti un periodo molto lungo ed è naturale che ora avvenga un “cambio della guardia” (c’è da dire che a Berlino spesso i mandati durano più che altrove, ma usualmente attorno dopo dieci anni il direttore di un teatro viene sostituito). Ecco dunque che due anni fa l’Assessore alla Cultura berlinese (il quale, tra l’altro, è stato recentemente sostituito) consiglia di nominare alla guida del Volksbühne il curatore belga Chris Dercon, direttore del Tate Modern di Londra e già anche direttore dell’Haus der Kunst di Monaco. Dercon ha certamente un profilo professionale prestigioso e riconosciuto ma nel contesto museale, non nel teatro! È vero, nel corso della sua carriera si è occupato anche di arti performative (ricordo una sua retrospettiva su Christoph Schlingensief al Tate) ma non è del tutto chiaro il perché sia stato scelto come direttore del Volksbühne. Credo comunque che la questione centrale sia la seguente: che cosa può offrire a questo teatro? Quali innovazioni possiamo aspettarci?

Guardando il suo programma per la prossima stagione sono molto scettico: per prima cosa si nota che è molto incentrato sulla danza (campo già esplorato al Volksbühne ma che non è mai stato fra le proposte principali). In più non ha costituito alcuna compagnia permanente di attori, il che è parecchio inusuale per un teatro stabile tedesco. La maggior parte delle perfomance inoltre consiste in “esibizioni” di produzioni esterne, che non verranno create in loco e avranno già esordito in altri teatri. Almeno per questo primo anno, la natura del Volksbühne sembra allora assumere in tutto e per tutto le caratteristiche di un festival internazionale di arte performativa.

Sembrerebbe che ci siano due diverse concezioni del teatro a confronto…

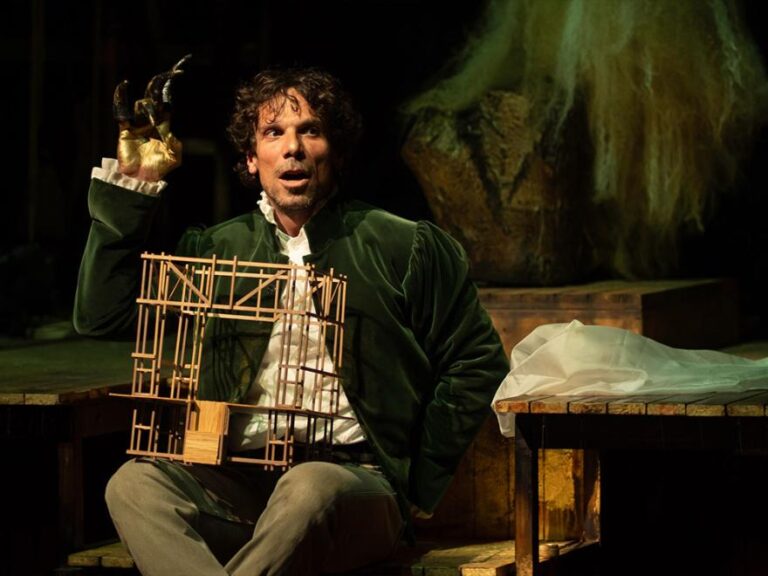

Non proprio. Fino a ora il Volksbühne è stato attraversato da pratiche sceniche di vario tipo, anche molto eterogenee fra loro, che però hanno sempre avuto un elemento portante: l’attore. Ogni regista che ha lavorato in questa struttura ha sempre potuto contare su attori di alto livello, partecipi del processo creativo. Si può infatti dire che il Volksbühne è un “teatro di attori”, con uno dei palchi più grandi al mondo che lo rende uno spazio veramente unico nel suo genere. Chi vi ha recitato dice che, nonostante l’ampiezza del palco, ci si sente comunque fortemente “vicini” agli spettatori. Ecco, io credo dunque che il Volksbühne sia uno spazio per un tipo di teatro il cui perno sia la recitazione, quale che sia l’approccio a essa o le tecniche attoriali utilizzate.

Quindi, tornando alla domanda di partenza, il confronto non è esattamente fra due diverse concezioni di teatro, ma fra un tipo di teatro che ha “bisogno” del posto in cui viene creato e che non può nascere altrove e questo stesso posto che però andrà sempre più ad assomigliare a una “sede polifunzionale” in cui nessuno si sentirà particolarmente attaccato alla struttura, con tutte le sue peculiari caratteristiche, né al pubblico che verrà ad assistere alle perfomance. Insisto, al momento non c’è nessun attore permanente assunto al Volksbühne fatta eccezione per tre performer rimasti dalla direzione precedente (che hanno lavorato nella struttura da abbastanza tempo per avere un incarico di ruolo) e non si capisce se o come saranno coinvolti nel processo creativo.

Dercon sostiene che in realtà non sta cambiando molto, in quanto l’organico del Volksbühne si è ridotto di molto durante la direzione di Castorf (in effetti erano presenti solo undici attori verso la fine del suo mandato) ma non tiene in conto quanto fosse stabile e radicata la compagnia: si trattava di attori che recitavano e provavano regolarmente con lo stesso regista e nello stesso spazio di prova. Lo stesso valeva per i registi che, come Cristoph Marthaler per esempio, costruivano saltuariamente i propri spettacoli al Volksbühne e che lavoravano “in residenza” con un gruppo di attori anch’essi ospitati durante i periodi di preparazione. Lo stesso avveniva per René Pollesch, in una certa misura. Così è stato per decenni e tutto questo ha creato un forte senso di connessione con la struttura, con il pubblico e con la condivisione di progetti e visioni teatrali. Senso di connessione che dunque ha costituito l’essenza stessa del Volksbühne. Mi pare che invece ora una simile attitudine sia andata completamente persa. Con Dercon, come ho detto in precedenza, il teatro assomiglierà sempre più a un festival internazionale e difficilmente si creerà un senso di appartenenza.

Questo processo di “internazionalizzazione” che descrivi è qualcosa di comune ad altri teatri della Germania? Diresti che si tratta di una tendenza in atto sulla scena europea?

Penso che in effetti ci sia una tale tendenza. Nel corso degli ultimi anni molti dei maggiori teatri tedeschi hanno acquisito un carattere più “internazionale”. Ovviamente si tratta in primo luogo del riflesso di un processo generale di cambiamento del paese, che si è fatto via via più europeo (in particolare se pensiamo a Berlino). Per esempio il Maxim Gorki, uno dei cinque teatri finanziati a livello statale, negli ultimi due anni si è sempre più reinventato come un teatro “multiculturale”. Quindi sì, è normale che esista un tale processo perché è una conseguenza dei cambiamenti che stanno interessando in generale le nostre società. Ma il punto ovviamente non è se il nuovo direttore sia o meno tedesco, o se lo siano o meno gli artisti e i performer (alcuni hanno bollato le critiche alla nomina di Chris Dercon come reazioni xenofobe, ma ciò è semplicemente assurdo…), il punto è quanto e come il processo di “internazionalizzazione” influenza il nostro modo di produrre e guardare il teatro. A questo proposito faccio un esempio: un teatro che a Berlino ha un forte carattere internazionale è lo Schaubühne. Le produzioni dello Schaubühne sono molto spesso in tournée, sono costantemente presenti nei maggiori festival internazionali, e io credo che proprio per questo i registi e gli attori sono spinti a produrre un teatro che è “compatibile a livello internazionale”. Voglio dire, esiste uno “stile internazionale” cui facilmente si adeguano (anche in maniera inconscia) quelle strutture che pongono l’andare in tournée e l’essere riconosciuti a livello internazionale al centro del proprio agire creativo. La mia opinione è che però questo tipo di teatro non potrà mai essere veramente radicale o innovativo. Al contrario, la stabilità e strutturale e lavorativa è molto spesso una condizione essenziale per il rinnovamento creativo.

Per questo penso che se anche il Volksbühne seguirà questo percorso di internazionalizzazione, perderemo un luogo di sperimentazione, un luogo in cui le idee artistiche vengano costantemente spinte fino alle loro estreme conseguenze e condotte a un grado di sviluppo più alto.

Poni infatti il “provincialismo” (o “localismo” che dir si voglia) al centro del processo di sviluppo teatrale. Perché pensi sia così importante? È sempre stato così per il teatro?

Il teatro accade in un dato momento e in un dato luogo. Non può che accadere in altro modo. Certo, puoi girare in vari paesi con il tuo spettacolo ma l’interazione che si crea con il pubblico sarà sempre qualcosa di diverso e mutevole. In un certo senso è molto affascinante osservare le reazioni di critici non tedeschi agli spettacoli provenienti dalla Germania. Ci sono elementi cui io, per esempio, non avrei mai fatto caso e altri che invece non possono essere compresi: i toni, le citazioni interne… Uno degli aspetti forse meno interessanti ma certamente più comuni a tanti teatri berlinesi è proprio quello di essere spesso autoreferenziali. Non si contano le battute provocatorie o le citazioni che si riferiscono ad altre performance del circuito e questa caratteristica era centrale in buona parte della produzione del Volksbühne.

E credo anche che un certo “localismo” o “provincialismo” (da intendersi come termine neutro) sia una componente presente nel teatro sin dai suoi albori. Se prendiamo Shakespeare, per esempio, possiamo rilevare processi molto simili a quelli che ho appena descritto, semplicemente perché gli attori del sedicesimo secolo si trovavano a operare in un contesto analogo: quattro-cinque teatri e compagnie stabili che lavoravano nella stessa città e si seguivano a vicenda. In altre parole, il teatro tende a generare delle “ecosfere” che creano reti e connessioni molto strette con le realtà vicine. Tuttavia, è proprio questo processo che consente lo sviluppo formale: si forma un “terreno comune” di sperimentazione, nonché una spinta alla competizione chiaramente, che permette ai vari autori di “appoggiarsi” ai lavori precedenti per provare ad “alzare l’asticella”. Si tratta di dinamiche proprie di quasi tutti i linguaggi artistici ma a mio modo di vedere nel teatro questo meccanismo è più intenso e cogente, per via di una maggiore prossimità con lo spettatore rispetto ad altre discipline e per il fatto che le opere si “trasportano” con maggiore difficoltà.

Inoltre, la Germania è forse un contesto in cui il “localismo teatrale” è più forte che altrove, dal momento che la maggior parte dei grandi teatri è finanziata dalle municipalità per cui, a un livello politico, il teatro è gestito dai poteri locali non dallo Stato federale. Anche per il Volksbühne è ovviamente così e se leggiamo le prime dichiarazioni di Castorf notiamo come avesse ben presente questo elemento. Poco dopo aver assunto la direzione del teatro, dichiarò infatti che avrebbe lottato per mantenere i prezzi dei biglietti bassi, come lo erano durante la DDR, per consentire anche agli abitanti del quartiere di continuare ad assistere alle performance e così fece. Si trattava di un genuino desiderio di restare un’istituzione culturale in primo luogo aperta alle persone che vivevano lì attorno. Tutto ciò è cambiato nel tempo, così come è cambiata la città: adesso i prezzi del Volksbühne si sono alzati e la struttura non riesce a essere così “aperta” come lo era prima. Allo stesso modo il quartiere è stato fortemente “gentrificato” e il pubblico di riferimento è cambiato parecchio. Ma mantenere viva l’idea di fondo per cui si debba fare teatro “per il popolo” (che poi è quello che la parola stessa “ Volksbühne” significa) è qualcosa di fondamentale per l’identità del posto e, soprattutto, non è minimamente in contraddizione con la volontà di produrre un teatro di avanguardia, sperimentale. Spesso si crede che l’arte sperimentale sia elitista ma non è il caso del Volksbühne, il cui ethos è invece sempre stato quello di offrire proposte provocatorie e “difficili” pur restando il più possibile inclusivo verso un tipo di pubblico popolare.

Come è cambiato allora il pubblico nel corso degli anni? Il Volksbühne ha sempre avuto un pubblico eterogeneo?

Il pubblico è cambiato molto. Sicuramente negli anni ‘90 era molto eterogeneo dal punto di vista sociale mentre col passare del tempo questo elemento di diversità interna si è un po’ perso. Uno degli episodi più famosi successe infatti proprio agli inizi della direzione di Castorf, durante la sua messa in scena di Arancia Meccanica. Improvvisamente la sala si riempì di skinhead, che seguirono lo spettacolo in maniera “parecchio rumorosa”, interrompendo spesso e lanciando oggetti contro gli attori. Difficile immaginare qualcosa di analogo successo negli ultimi anni… tuttavia esiste certamente un gruppo di frequentatori assidui molto diversi fra loro (si può vedere dalle loro proteste su Facebook nei confronti del nuovo direttore), non solo studenti o artisti ma qualsiasi tipo di persona che vive nel quartiere e sente una forte connessione con il posto.

C’è da dire che un tale contesto ha anche generato una certa “chiusura” per cui alcuni spettacoli avevano un carattere veramente troppo autoreferenziale, si trasformavano in una sorta di “gioco per un gruppo di iniziati” (un gruppo di iniziati comunque sempre molto numeroso) per cui uno spettatore esterno si poteva sentire escluso e spaesato. Questo ha certamente a che fare col fatto di essere la stessa compagnia per 25 anni.

Insomma il Volksbühne ha avuto i suoi alti e bassi, come qualsiasi altro teatro d’altronde. Già nel 1993 uscivano recensioni che descrivevano lo stile di Castorf come prevedibile e affermavano che la maggior parte degli spettatori si stava disinnamorando del teatro (tra l’altro questa critica è stata ripresa negli ultimi tempi dalla stampa di destra). All’inizio degli anni 2000 poi si è verificato un serio “crollo”, con il pubblico ridotto a pochi spettatori e numerosi riscontri negativi da parte della critica. Ma Castorf ha una speciale capacità di “intercettare” sempre nuove fonti di energia creativa, di “rinnovare” le sue ossessioni e preoccupazioni artistiche e gli spettatori sono ogni volta tornati a riempire la sala. Soprattutto negli ultimi due anni il Volksbühne aveva trovato nuove e convincenti linee di esplorazione e innovazione, anche per questo che forse la protesta contro Chris Dercon è stata così sentita.

C’è poi un altro elemento: Castorf è sempre stato un regista forte e dominante ma il suo stile è anche frutto di collaborazioni molto strette: basti pensare a Bart Neumann, il grande e influente designer che ha costruito la maggior parte dei “set” di Castorf e a cui dobbiamo l’aspetto inconfondibile del Volksbühne. Inoltre ci sono stati registi lontani dal metodo e dall’approccio di Castorf che hanno prodotto saltuariamente spettacoli per il Volksbühne e nel Volksbühne, facendone una seconda casa. Penso a registi quali Marthaler, Schlingensief, Pollesch e più recentemente Herbert Fritsch… questo mette in crisi l’argomento per cui il Volksbühne negli ultimi 25 anni avrebbe coltivato in maniera eccessivamente nostalgica un’identità “est-berlinese”. In una certa misura lo ha fatto, ma quasi tutti i registi che vi hanno collaborato non provengono dalla ex-DDR e così i drammaturghi o gli attori.

Dunque insisto sul fatto che la controversia attuale non riguarda da dove proviene il nuovo direttore Chris Dercon ma verso dove si sta dirigendo la sua conduzione artistica, riguarda il fatto che non si sta chiedendo in alcun modo cosa può fare per il posto specifico che è chiamato a gestire e, in ultima istanza, non si sta chiedendo a chi è rivolta la sua offerta teatrale.

[ENGLISH VERSION]

In your article you firmly criticize the decision to appoint Chris Dercon to the direction of the Volksbühne. Why?

It’s worth briefly summarizing the history of the theater: the Volksbühne has been around for over 100 years and it has been a touchstone not only in Germany but for international theater as well, and it was always challenging the political status quo as well. In the 1920s, under Piscator, it was one of the major influences for Brecht; in the GDR it was a place where a sort of counter-cultural theater could happen at least for a while during the 70s, and then in the 90s, right after the reunification, the Berlin Government surprisingly appointed Frank Castorf, who was very young at the time, and had a reputation as a rebel. If you read Castorf’s early interviews he was saying that he had no idea why they would trust him with that place. But he thought (as did the committee that recommended him) that within a few years, they’d either be famous or bankrupt.

Under Castorf’s direction, for the next 25 years and with some ups and downs, the Volksbühne became a real growth-cell for theater development in Germany and in the whole of Europe; it became a place international theater artists were looking to for inspiration. But Castorf also lasted far longer than most artistic director do in Germany (Berlin is a bit different from most other cities in this, but usually after about 10 years you would expect a change of the guards in most places).

So two years ago the politician who was in charge of the Department of Culture in Berlin (who is no longer in office now, by the way) recommended that Castorf’s contract not be renewed and that the new artistic director of the Volksbühne should be the director of Tate Modern in London, Chris Dercon, a Belgian curator. Dercon used to run the Haus der Kunst in Munich, he has a very high profile… but in the museum world, not in theater. So it was not that clear why they chose him to run one of the major theaters in the country, even though he had done installation and programming with performance art in the places he worked in (a retrospective of Christoph Schlingensief at the Tate, for instance). There’s a real question what exactly he can he bring to the Volksbühne. If you take a look to the program he presented for the upcoming season you will notice that it is heavily focused on dance (something that of course happened at the the Volksbühne before, but it wasn’t really the core of the programming there). Moreover, Dercon hasn’t established a real fixed ensemble, which is very unusual for a major German theater, since every city or state theater has its own ensemble. Most of the performances he has programmed are being put together somewhere other than in Berlin and will be just presented at the the Volksbühne, in some cases not even for the first time. So the character of the institution appears about to change in the direction of an ongoing festival of international performance art of various kinds, at least for the first year of Dercon’s administration.

It looks like there are different two ways of conceiving theater that are confronting each other…

It’s not even two ways of thinking about theater. From the point of view of artistic conceptions what has been happening until now at the Volksbühne has been very diverse, but there has always been an essential element: the actor. Every director who worked there under Castorf relied on extremely committed performers. We can say that the Volksbühne is an actors’ theater, it’s a theater with one of the greatest stages in the world – it’s a unique performance space. Actors often say that even though it’s a very large stage you can always feel the audience around you. The Volksbühne is a place for a kind of theater that depends on acting, but it also supports a very wide range of different approaches to acting, to performance.

In my opinion the big contrast is that until now you have had a theater that needed this building and could only be made there; while under the new regime it’s just going to be a venue, where no one will be particularly attached to the building or to the people who come to see the shows there. Again, only a tiny number of actors are permanently employed at the Volksbühne now: there are three performers left (the ones who couldn’t be fired, because they had been in the ensemble for long enough to essentially have tenure) but it’s totally unclear in what way they are going to be involved in the artistic process of the theater, if at all.

Dercon claimed that it’s not changing that much since the the Volksbühne’s ensemble had shrunk under Castorf (it had only eleven members at the end) but he’s ignoring that a large group of actors were consistently working there over years even without choosing to join the ensemble: a lot of the actors were regularly collaborating with the same directors on that stage. Christoph Marthaler frequently directed at Volksbühne since 1992, and he has his own fairly fixed group of actors, most of whom aren’t in the ensemble as such, but they would come to rehearse at the Volksbühne for weeks and months at a time. Same, to a degree, with René Pollesch. They’ve been doing this for decades. So this sense of connection, connection to the place, to the people, to the work, to a shared project has been absolutely at the core of the Volksbühne’s way of working. That is completely gone now and it’s not replaced with any alternative. On the contrary, Dercon’s model seems to be the one of an international festival which will hardly produce a sense of belonging.

Would you say that the pattern of “internalization” of theaters and theater festivals is trending in Germany and in Europe?

To some extent I’d say it’s trending. A progressive internalization of some of the major theaters in Germany has happened during the recent years and it probably just reflects the general change of the country which has become – of course – more and more European and diverse (especially in Berlin). The Maxim Gorki Theater, which is one of the five state-funded theater of the city, has been reinventing itself in the last couple of years as a multicultural theater. So on the one hand it’s completely normal, and important, that theater reflects that general context. The problem isn’t with directors and actors coming from a variety of cultures and backgrounds (some critics have said the response to Dercon’s appointment is xenophobic, but I think that’s ridiculous: people are upset about what he is doing, not about where he’s from). The problem lies in how a kind of international performance scene is affecting our ways of doing and seeing theater. For instance, the other Berlin theater which is very international is the Schaubühne; they are constantly touring their productions, they are regularly present in the major international theater festivals, and I think that, since touring is so much at the core of their work, they tend to produce (not in a deliberate way, but probably unconsciously) a theater which is more “internationally compatible”. I think we can say that there is a sort of “international theater style” and in my opinion, it’s precisely because it’s so international that it’s less radical, less cutting edge.

My worry is that if the Volksbühne is going to follow this international path, we will lose a place for experimentation, where art is pushed further and further in a particular context. In fact the stability of working conditions at the old Volksbühne allowed directors and actors (and designers!) to explore and push every artistic idea to its limits and then take the next step. If we lose places where such a way of making theater is possible, we’ll lose the possibility for any development.

In fact you claim that “provincialism” or “localism” is a feature at the core of the theater-making process. Why it is so important? Would you say it’s a recent phenomenon or it has always been the same in the history of theater?

Theater happens in a particular place at a particular time. It cannot happen other way. You can go on tour with a show but the audience is different and it will respond differently. It’s fascinating to see non-German speaking critics’ responses to German theater because there are things they notice that I – for instance – would have never noticed and some others they just miss: tone, references… one of the maybe less interesting but very present features of a lot of Berlin theaters – and the Volksbühne in particular – is that they are intensively self-referential. They love making bad jokes about other shows or to quote other shows. Playing with what the audience expects and knows is pretty central to their work.

And yes, I’d say provincialism (as a value-neutral term) is a constant feature of theater. If you take Shakespeare, for instance, you can find a lot of similar processes. Because actors in 16th-century London were working in similar conditions: four or five stable theaters and companies knowing each other’s shows. Theater tends to create an “ecosphere” where networks or meaning are created. On the other hand that’s precisely one of the mechanisms which allow development: every theater can build upon other theaters’ work. On the other hand, there is a sort of common ground and competition as well. Of course these are general dynamics of many kind of arts but in theater they are probably exacerbated because of the closeness with the audience, and because it’s much harder to transport: the networks are more local, more direct. You actually have to be there to see other shows, to see how people respond, etc.

Also, in Germany this is even more pronounced than in other countries since theater has usually a strong institutional component: every major city has its own theater, most theaters are primarily funded by the city or the province. So at the political level theater is a concern of the locality, not of the federal state. This was true for the Volksbühne as well. Some of Castorf’s early statements were going in this direction: he fought to maintain low ticket price as they were before the fall of the wall, because he really wanted everyone in the neighborhood to still be able to come to the theater. There was a genuine desire to be open to everyone around the Volksbühne and around the company coming into the theater and being part of it. That has shifted a bit as Berlin has changed: the Volksbühne’s tickets aren’t all that cheap anymore and the neighbourhood has changed pretty dramatically: it’s massively gentrified, and you can see that in the audience too. But still, trying to keep alive the fundamental idea of making theater for the people (which is what “Volksbühne” means, after all: “the people’s stage”) has been crucial for the identity of the place itself. And even more important: all of this is by no means in contrast with experimenting and making an avant-garde sort of theater. We tend to think that avant-garde theater is elitist, but that has never been the case for the The Volksbühne which had the ethos to challenge its audience while engaging them to come and see.

How has the Volksbühne audience changed over the years? Would you say it’s generally diverse?

The audience has changed a lot. I’d say the Volksbühne during the 90s had a very diverse audience, socially at least, while in recent years it’s probably been getting more and more homogeneous. One of the famous episode of Castorf’s tenure happened in the early 90s during the stage of his Clockwork Orange: suddenly they were getting lots of skinheads in the audience, East-German kids quickly radicalized after the wall came down, who were upset by parts of the show and started throwing stuff at the actors. I can’t imagine something like that happening in the last few years.

But still, there is a core group of aficionados which is pretty diverse (you can see it on Facebook protesting against the new artistic director): it’s not just academics and students and artists but all kinds of people who are living in the neighborhood and who feel a strong connection to the place.

On the negative side, I have to say that some of the shows became maybe too self-referential, a bit self-congratulatory, a sort of closed game for an in-crowd (if a large in-crowd), and someone not part of it could find him- or herself pretty alienated. This has of course something to do with being the same company for 25 years. . And like many other theaters, the Volksbühne had its ups and downs, going trough uninspiring phases even in the early years. Already in 1993 you can find reviews saying that Castorf’s work had become predictable and that the majority of the spectators had left the theater (funny enough, last year’s German conservative newspapers where saying exactly the same). Then at the beginning of the 2000s, there was a pretty serious slump, with poor audience numbers and lots of disappointing reviews. But Castorf has a knack for discovering new sources of energy, new obsessions, or new ways of engaging his old preoccupations, and in the end people always came back. Especially in the last few years he’s produced really exciting and challenging work, and this is also one of the reasons why protests against the end of his mandate were so loud: it was a “why now?” reaction.

There is also another element. Castorf has always been a dominant director but he found other people who made the Volksbühne their home. His own work is really inseparable from that of Bert Neumann, the great, hugely influential designer who built most of Castorf’s sets and was responsible for the Volksbühne “look” in general. And then there were the other really important directors, whose work and attitude are very different from Castorf’s own: Marthaler, Schlingensief, Pollesch, and most recently Herbert Fritsch.

And if you look at those theatremakers, it kind of undermines the idea that Castorf’s Volksbühne had this nostalgic East-Berlin identity, always longing for what was lost with the end of the GDR. It did to some extent of course, but many of the directors who have worked there aren’t from the former GDR at all, and the same is true of the actors and some of the dramaturgs. So again, it’s not about the fact that someone from elsewhere is coming to the Volksbühne. That was happening under Castorf already, from the very start. The point is that it feels like the new director is not coming for the Volksbühne, like he hasn’t really taken seriously the question of what he can do for that particular place and, even more importantly, of who he wants to make theater for. What this place is and has been, what opportunities and challenges it offers, what it demands, what it needs, what it can do.

L'autore

-

Giornalista e corrispondente, scrive di teatro per Altre Velocità e segue il progetto Planetarium - Osservatorio sul teatro e le nuove generazioni. Collabora inoltre con il think tank Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso Transeuropa, occupandosi di reportage relativi all'area est-europea.