Questa intervista fa parte dell’Osservatorio sulle arti infette, un progetto realizzato nell’ambito del Laboratorio avanzato di giornalismo culturale e narrazione transmediale organizzato da Altre Velocità: si tratta di una serie di conversazioni che le partecipanti al laboratorio hanno condotto con artisti, operatori e studiosi per indagare i mutamenti e le difficoltà del teatro rispetto alle conseguenze della pandemia del Covid-19.

Intro: Children’s gaze

Chi da bambino non è rimasto incantato ad ascoltare storie lette ad alta voce da nonni e genitori, di struggenti storie d’amore e rocambolesche avventure di pirati e briganti?

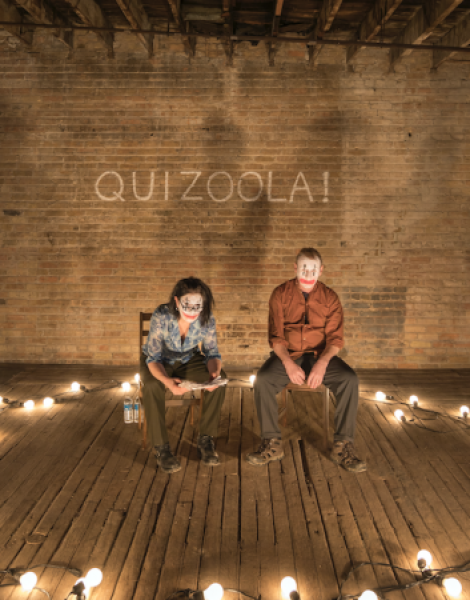

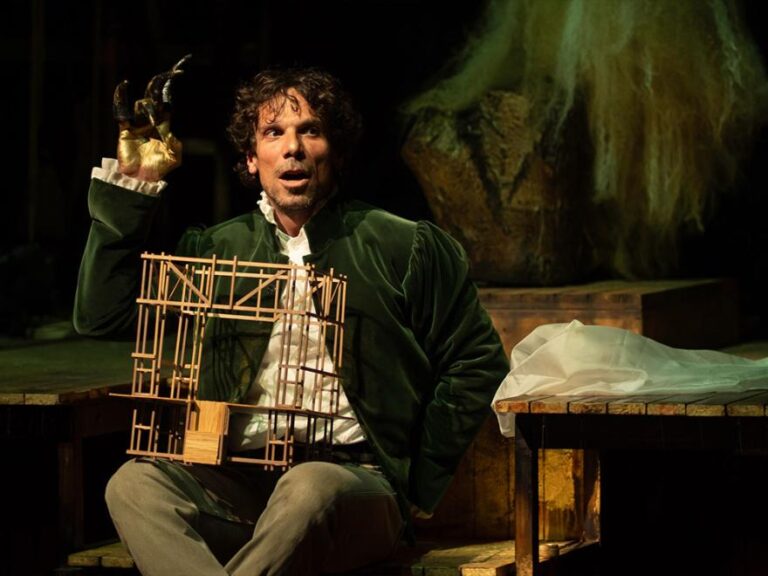

In un periodo in cui i teatri sono luoghi inaccessibili, abbiamo provato a esplorare nuovi modi per rimanere spettatori. Tra le varie proposte di teatro online ci siamo imbattute in una serie di spettacoli particolari, in cui oggetti quotidiani all’apparenza insignificanti diventano protagonisti di racconti universali. In Complete Works: Table Top Shakespeare l’intera produzione del Bardo viene portata in scena nelle case degli attori della compagnia inglese Forced Entertainment. Tre appuntamenti alla settimana – per un totale di dodici settimane – che sono diventati un mezzo per scandire i tempi della quarantena. Un’occasione per non perdersi nel grigiore di una domenica costante.

Sul palco – il tavolo di una cucina – il narratore racconta le vicende dei personaggi shakespeariani manipolando bottiglie di olio, vino, tabasco, flaconi di shampoo e sapone, accendini e pacchetti di sigarette. I protagonisti, astratti e incarnati in articoli familiari e comuni, mantengono tutta la loro potenza epica.

Abbiamo intervistato Claire Marshall e Richard Lowdon, tra i fondatori del gruppo, per discutere della genesi del progetto e ragionare insieme intorno alle possibilità del digitale a teatro. Tramite parole chiave – absence, digital spaces, digital audience, imagination e safety net – abbiamo lasciato la parola agli attori, in modo da restituire una panoramica il più possibile completa del nostro confronto.

Oggi nessuno ci racconta più le fiabe, ma in un periodo complicato come questo, troviamo conforto proprio in quelle storie che guardavamo o leggevamo durante l’infanzia. I Forced Entertainment hanno preso il posto di quelle calde voci familiari che ci cullavano da bambine, facendoci provare le stesse emozioni di stupore e meraviglia. Forse, abbiamo solo bisogno di immaginare.

Absence

Richard: «Già prima della pandemia eravamo impegnati a lavorare su spettacoli accessibili anche digitalmente. Fra le prime esperienze ci sono state le durational performance, ovvero pièce molto lunghe – di circa sei ore e perlopiù improvvisate – portate in scena live e al tempo stesso trasmesse in streaming, in modo tale da permettere al pubblico una fruizione più libera e autonoma. Lo stesso abbiamo fatto con The Complete Works nel 2015: il pubblico (un gruppo di circa 40-50 persone) era insieme a noi in una piccola stanza e sedeva attorno al tavolo, abbastanza vicino per poter vedere gli oggetti muoversi e agire. Desideravamo fare uno spettacolo per un pubblico in presenza, e lo streaming faceva solo da supporto per ampliare il bacino di utenza. Con la pandemia, ci siamo resi conto che The Complete Works poteva essere un buon progetto per una proposta totalmente in digitale, non solo per la brevità delle pièce, ma anche per la sua genesi e il tipo di formato: fare uno spettacolo a partire dal tavolo della cucina e da oggetti quotidiani ci è parso una sorta di atto di generosità per il momento che stavamo vivendo, la possibilità di parlare da casa a casa».

Claire: «Altri di noi ovviamente hanno sperimentato altri modi per affrontare la situazione. Per esempio una nostra amica, l’artista Ester Chinningwith, ha ideato un progetto chiamato Care Taker alla Royal Court di Londra. Con i suoi collaboratori hanno posizionato una telecamera nello spazio vuoto del teatro e l’hanno fatta girare per l’edificio per almeno tre settimane. La performance consisteva semplicemente nell’attraversamento di questo spazio senza niente e nessuno, con una voce che spesso parla e racconta delle cose che stanno lì attorno. È stato bello, un modo per parlare e toccare con mano l’assenza».

Richard: «Un’altra idea che abbiamo trovato interessante sono stati gli spettacoli del comico Daniel Kitson: ha girato in tour per il paese esibendosi in teatri vuoti. Gli spazi vendevano i biglietti in numero pari ai posti che si possono occupare in sala, poi la performance è stata resa disponibile su Vimeo tramite link d’accesso».

Digital spaces

Richard: «Il primo progetto proposto nella prima fase di pandemia è stato End meeting for all, uno spettacolo inizialmente pensato per la messa in scena dal vivo che per ovvie ragioni non si è potuto realizzare. Abbiamo così deciso di adattarlo al solo digitale, registrando la performance su Zoom e poi condividendola senza editing sulla medesima piattaforma. Proponendo un video pre-registrato senza alcun montaggio, volevamo che il pubblico vivesse una sorta di esperienza senza tempo, ma con tutte le imprecisioni, l’insicurezza e la naturalità della live. In fondo gli errori e la stupidità ci fanno sentire parte del genere umano, e oggi più che mai credo sia importante provare ad agire in tal senso. Queste prime esperienze su Zoom ci hanno però posto di fronte al desiderio di trovare un modo per non restringere il numero di partecipanti, ma rendere i contenuti quanto più accessibili possibile. Inoltre molti sono i partner che ci hanno aiutato a produrre The Complete Works e volevamo una piattaforma che rendesse facile per tutti la ri-condivisione sui propri siti e pagine. YouTube quindi ci è parso lo spazio più facile e più largamente conosciuto dove caricare i nostri lavori. In un certo senso scegliendo YouTube abbiamo optato per la strada della parità».

Claire: «Penso che YouTube sia la piattaforma migliore in questo senso. Anche i grandi teatri utilizzano il loro canale – magari già in funzione prima della pandemia – per caricare le loro produzioni o alcuni lavori pre-registrati, oppure per creare performance a pagamento. In questo senso i teatri stanno facendo davvero del loro meglio per rendere i loro programmi accessibili al pubblico, sia in presenza che online. Infatti molti spettacoli dal vivo vengono contemporaneamente trasmessi in streaming; perciò spesso online ci si confronta con performance pensate per il live ed è inevitabile che alcune funzionino meglio di altre. A me e Richard è capitato di non poter raggiungere il teatro a causa del lockdown della nostra città, perciò abbiamo guardato lo spettacolo in streaming: si poteva sentire quanto piccola fosse la presenza del pubblico in sala».

Digital audience

Richard: «Ciò che è cambiato con l’arrivo della pandemia è ovviamente la percezione della totale assenza di pubblico. Tutti noi ci siamo sentiti soli, seduti in quella stanza davanti a un computer a registrare e muovere cose sopra a un tavolo senza nessun altro attorno. Chiaramente quando c’è il pubblico lo percepisci, senti le risate, i lamenti, la loro attenzione, la loro calma improvvisa, cose che inevitabilmente perdi quando ti ritrovi a fare qualcosa solo per il digitale. In quei momenti si lavora davvero da soli, seguendo il ritmo e il senso di come potrebbe essere se fossimo noi gli spettatori. Un altro aspetto strano della questione è la sensazione di averlo già fatto: quando il lavoro viene diffuso online, siamo noi i primi spettatori della nostra stessa performance, principalmente per controllare se si viene a creare una sorta di connessione attraverso tweet e commenti. Il problema quindi di provare a fare teatro attraverso i media digitali per l’attore è l’assenza di feedback continui che si percepiscono solo quando attori e spettatori sono co-presenti in uno spazio-tempo».

Claire: «Penso che da questa esperienza abbiamo anche scoperto delle cose. Nel momento in cui le performance vengono diffuse online, le persone non necessariamente guardano la pièce la sera stessa, ma potrebbero fruirne in un altro momento. Spesso ci arrivano delle mail, altre volte apriamo la chat, altre ancora abilitiamo i commenti: si ha così un più lungo e lento senso di costruzione di una piccola comunità. Inoltre, finita la messinscena, si ha la forte sensazione della presenza di persone da tutto il mondo che attendono con piacere l’uscita dei nostri contenuti. Quello che abbiamo scoperto, dunque, credo sia la consapevolezza che se riesci a essere abbastanza generoso, è possibile creare connessioni che non saresti in grado di costruire in altre circostanze. Penso che in questo ci sia una sorta di livellamento, una specie di equità: come noi dobbiamo essere generosi, così il pubblico ha bisogno di esserlo altrettanto.

Esperienze simili chiedono, per certi versi, molte “insurrezioni”, molto intervento e credo che sia una buona cosa. In generale nel pubblico digitale abbiamo trovato reazioni curiose: durante End meeting for all avevamo deciso di lasciare la chat aperta, le persone potevano comunicare fra loro in tempo reale e questo è effettivamente avvenuto, specie quando il divertimento cresceva. È questo che fa sentire gli spettatori connessi, anche se è particolarmente strano per un artista, dal momento che a teatro l’ultima cosa che dovresti fare durante uno spettacolo è chiacchierare. Con The Complete Works abbiamo invece deciso di disabilitare i commenti su YouTube, anche per una certa paura di imbatterci in episodi spiacevoli, ma soprattutto per capire che cosa succede se si toglie al pubblico digitale la possibilità di risposta in tempo reale. La cosa interessante è che di fondo la connessione fra il gli spettatori non sparisce…»

Richard: «Per fare un esempio a riguardo, durante End of the thousand night (una pièce narrativa di circa sei ore, perlopiù improvvisate e senza fine, in scena live e trasmessa contemporaneamente in streaming) abbiamo visto come improvvisamente a un certo punto le persone hanno iniziato a scrivere momento per momento su Twitter cosa stava accadendo, ciò che faceva loro ridere, e così via. Abbiamo allora capito che forse questo genere di interazioni potrebbero diventare un modo per le persone di sentirsi parte di qualcosa, partecipi insieme a un evento, sebbene a distanza».

Claire: «A questo proposito, mi piace ricordare due nostre spettatrici, due sorelle dagli Stati Uniti, che penso vivessero lontano l’una dall’altra e che non si vedessero ormai da anni. Hanno tuttavia voluto guardare i nostri lavori su Shakespeare insieme, e quindi chattavano fra di loro mentre partecipavano alla visione della performance. Penso che queste connessioni, questo bisogno di sentirsi insieme esista al di fuori delle nostre possibilità. In fondo, guardare qualcosa davanti a uno schermo per conto tuo ti fa sentire davvero solo».

Imagination

Richard: «In questi anni abbiamo lavorato molto sul concetto di teatro: in alcuni casi volevamo creare cose molto rumorose e caotiche, in cui gli occhi non sanno dove posizionarsi – un piacere proprio del teatro che il cinema è impossibilitato a riprodurre – e dove lo spettatore è chiamato a confrontarsi costantemente con ciò che si trova davanti. Altre volte invece, abbiamo preferito togliere tutto dal teatro: nella performance Dirty Work due persone parlano di uno spettacolo mai andato in scena, raccontando solo l’inizio del primo atto. La performance obbliga il pubblico a immaginare lo spettacolo. In The Complete Works lo spettatore deve immaginare che gli oggetti siano dotati di sentimenti e di desideri, capire quando sono tristi e quando felici. Forse è questo il cuore della narrazione: aprire una minuscola porta per l’immaginazione e chiedere al pubblico di riempire i dettagli».

Claire: «Nel nostro lavoro siamo più interessati alle domande che alle risposte. Da tempo ragioniamo su che cosa significhi raccontare una storia, dire una bugia, dire la verità, che cosa vuol dire essere un personaggio, fingere di essere qualcun altro. Ci piace che queste cose siano molto complicate, in The Complete Works la narrazione si concentra intorno all’oggetto della storia, noi attori rimaniamo in sottofondo: quando recito la parte di Caterina in La Bisbetica Domata, non sono io, ma lei. In un certo senso sono solo fiabe, da cui puoi prendere ciò che vuoi».

Safety net

Claire: «In generale nel nostro settore penso che la pandemia abbia portato le persone a pensare molto riguardo a cosa vogliono dire e fare attraverso il loro lavoro, e a interrogarsi su che cosa sia l’arte. C’è molto cuore in quello che facciamo, perché in fondo l’arte è vita. Non posso dire con sicurezza a che punto siamo tutti noi in quanto comparto artistico-culturale, ma penso che ci si stia interrogando molto in questo periodo e questo non è affatto negativo. In fondo sta accadendo qualcosa di estremamente grande a tutta l’industria culturale e il teatro non può che fare i conti con questo».

Richard: «Sì, questa situazione obbliga a porsi delle domande riguardo alla natura stessa del teatro, specie quando ci si ritrova a confronto con le restrizioni anti-Covid, come quella che prevede che i performer in scena debbano stare a un metro e mezzo di distanza gli uni dagli altri. Allora inizi a chiederti: in quale tipo di esperienza teatrale stiamo cercando di tornare?

Da quando il vaccino è disponibile le cose sono cambiate, perché si può pensare che prima o poi i teatri riapriranno senza restrizioni. Ma questa situazione è da prendere come una sfida del tutto positiva, perché ci invita a porci domande complesse che altrimenti non ci saremmo posti».

Claire: «A livello politico, invece, il governo inglese sta supportando gli artisti: noi personalmente siamo in una buona posizione, lo stipendio è ridotto ma lo riceviamo. Molte persone come i liberi professionisti, i freelance, i costumisti e i light designers non stanno altrettanto bene, sono caduti tra le maglie della rete di sicurezza. Per molte persone la situazione è difficile e probabilmente alcuni non riusciranno a riprendersi. Forse il vaccino potrà mettere freno alla situazione; ma penso comunque che ci porteremo dietro le conseguenze di questo periodo per molto tempo».

Richard: «La nostra compagnia è stata fortunata, siamo attivi da trentasei anni e questo è quello che facciamo per vivere, perciò non siamo nella stessa posizione degli attori che stanno cercando lavoro. Tuttavia credo che l’amministrazione inglese stia facendo un buon lavoro: abbiamo molto per cui essere grati e non stiamo morendo di fame».

Outro: disappear into darkness

Claire: «Penso che gli spettatori siano molto affamati. In che altro modo si può dare senso a ciò che sta accadendo? In quale modo poterlo descrivere?»

Richard: «The Complete Works, nella cornice della pandemia, è simile al Decamerone di Boccaccio: mentre fuori la peste infuria, dentro casa raccontiamo storie. Questo atto ci permette di conquistare del tempo per pensare, fuggire e creare spazi di discussione. Parlare e ragionare su questo momento – come stiamo facendo ora – è prezioso. Aiuta tutti a non cadere nella solitudine, a non sparire nell’oscurità».

(english version)

Maybe we just need to imagine. Interview with Forced Entertainment

Intro: Children’s gaze

Who, as a child, has not been enchanted by stories read aloud by grandparents and parents, of poignant love stories and daring adventures of pirates and brigands?

At a time when theatres are inaccessible places, we have tried to explore new ways to remain spectators. Amongst the various online theatre offerings, we came across a series of unusual shows in which seemingly insignificant everyday objects become the protagonists of universal stories. In Complete Works: Table Top Shakespeare the entire production of the Bard is staged in the homes of the actors of the English company Forced Entertainment. Three appointments a week – for a total of twelve weeks – which have become a way of marking time in quarantine, an opportunity not to get lost in the greyness of an endless Sunday.

On the stage – a kitchen table – the narrator tells the story of the Shakespearean characters by manipulating bottles of oil, wine, tabasco, shampoo and soap, lighters and cigarette packets. The protagonists, abstracted and embodied in familiar and common items, retain all their epic power.

We decided to interview Claire Marshall and Richard Lowdon, two of the group’s founders, to discuss the genesis of the project and to reason together about the possibilities of the digital in theatre. Using key words – absence, digital spaces, digital audience, imagination and safety net – we let the actors speak, in order to give an overview as complete as possible of our discussion.

Nowadays, no one tells us fairy tales anymore, but in a complicated moment like this, we find comfort in the stories we used to watch or read during our childhood. The Forced Entertainment shows have taken the place of those warm, familiar voices that lulled us as children, making us feel the same emotions of awe and wonder. Perhaps, we just need to imagine.

Absence

Richard: «When the pandemic first happened, we were already engaged in making our work available digitally. The first experiences we made online were the durational performances. They were quite long piéce (approximately 6 hours long and largely improvised), performed live and streamed at the same time, in order to allow the audience to enjoy the play more freely and independently. We did the same the first time we made Complete Works – Table Top Shakespeare: the audience (a group of about 40-50 people) was with us in a small room, sitting around a table, quite close, ready to be able to see the objects move and act. So, when we first made these plays, the initial attempt was to perform live while reaching a wider audience, outside of the room. With the arrival of the pandemic, we just realized that Complete Works was a nice project to make it only digitally, both because the plays are short and for the genesis of the format. Given the time we were living through, it seemed to us an act of generosity to perform from a kitchen table using everyday objects and also a possibility to talk from home to home».

Claire: «Others of us, of course, tried different ways to deal with the situation. For example, a friend of ours, the artist Ester Chinningwith, came up with a project called Care Taker at the Royal Court in London. She and her co-workers placed a camera in the empty spaces of the theatre, and the camera has run around the building for at least three weeks. The performance simply consisted of walking through this space with nothing and nobody. Quite often, a voice speaks and tells about the things around it. It was beautiful, a way of talking about and touching absence».

Richard: «Another idea we found interesting were the shows of comedian Daniel Kitson. He toured the country performing in empty theatres. The venues sold tickets in numbers equal to the number of seats that could be occupied in the theatre, then the performance was available on Vimeo via an access link».

Digital spaces

Richard: «Our first project as the pandemic hit was End meeting for all. Initially conceived for a live audience, that could not be realised because of obvious reasons. So we decided to adapt it only for digital space: we recorded the performance on Zoom and then we shared it without editing on the same platform. By offering a pre-recorded video without any editing, we wanted the audience to have a sort of timeless experience with all the inaccuracies, insecurities and naturalness of live performance. I suppose that mistakes and stupidity make people feel like people, and today – more than ever – I think it’s important to try and do that. This first experience on Zoom, however, confronted us with the desire of finding a way not to restrict the number of participants, but to make our contents as accessible as possible. In addition, there are many partners who have helped us to produce Complete Works and we wanted a platform that would make it easy for everyone to re-share the contents on their own sites and pages. YouTube therefore seemed to us the easiest and most widely known place to upload our works. In a way, by choosing Youtube we opted for the path of equality».

Claire: «I think YouTube is the best platform in this sense. Even big theatres are using their youtube channel – often already in place before the pandemic – to upload their productions, some pre-recorded works, or even to create paid performances. In this sense, theatres are really doing their best to make their programmes accessible to the audience, both in presence and online. In fact, many of live performances are simultaneously streamed, so online you can find plays designed for liveness, and it’s inevitable that some work better than others. Richard and I happened to be unable to get to the theatre because our city was in lockdown, so we watched the show via streaming: you could feel how small the audience presence was».

Digital audience

Richard: «What changed with the pandemic was the obvious perception of the total lack of the audience. We all felt alone, sitting in that room in front of a computer recording and moving things on a table with no one else around. Obviously when there’s an audience you feel it, you hear the laughter, the moaning, their attention, their sudden calm. These are things you inevitably lose when you find yourself doing something just for the digital space. In those moments you are really working on your own in kind of rhythms and sense of how it would be received. Another strange aspect of the question is the feeling of having already done it: when the work is online, we are the first spectators of our own performance, mainly to check if a sort of connection is created through tweets and comments. So, I suppose that the main problem for actors is trying to make theatre through digital media is the lack of the loop of feedback, which is only felt when actors and spectators are together in the same space and time».

Claire: «I agree with Richard saying that we all miss the audience and the lack of the liveness of performance, because we lose something concerning life, in a way. However, I think we have also discovered things from this experience. When performances are broadcast online, people don’t necessarily watch the play that night, they might enjoy it at another time. Often, we get emails, other times we open the chat or we enable comments, so there is a longer and slower sense of building a little community. By the time we finished performing them, we felt a strong sense of people from all over the world waiting with pleasure for our contents to come out. So, what we have discovered, I think is an awareness that if you are prepared to be generous enough, then you can make connections that you wouldn’t be able to do in different circumstances. I think there’s a kind of levelling out in that, a kind of fairness: just as we need to be generous, the audience needs to be generous too.

In some ways, these experiences ask for quite a lot of insurrection, a lot of intervention, and I think that’s a good thing. In general, we found curious reactions in the digital audience. During End meeting for all we decided to leave the chat open, so people could communicate with each other in real time and this actually happened, especially when the fun was growing. That is a way the audience can feel connected, even though it’s particularly strange for an artist because in theatre the last thing you should be doing during a performance is chatting. Then with Complete Works we decided to disable comments on YouTube – admittedly out of a sort of fear to get some really unpleasant episodes – but above all to understand what happens if you take away the digital audience’s ability to respond in real time. The interesting thing is that the connection between the audience does not basically disappear…»

Richard: «To give an example, during End of the thousand night (a storytelling piece of about six hours, mostly improvised and without end) performed live and simultaneously streamed, we saw that at a certain point suddenly people started to tweet moment by moment about what was happening, what made them laugh, and so on. Then we realised that maybe these kinds of interactions could become a way for people to feel part of something, to be part of an event together, despite distance.

Claire: «In this regard, I like to remember two of our viewers, two sisters from the US, whom I guess live far away from each other and have not seen each other for years. They nevertheless wanted to watch our work on Shakespeare together. So they chatted with each other while they were watching the performance. I think these connections, this need to feel together, exist outside of our possibilities. After all, watching something in front of a screen on your own makes you feel really lonely».

Safety net

Claire: «In general in our industry, I think the pandemic has led people to think a lot about what they want to say and do through their work and to question what art really is. There is a lot of heart in what we do, because art is life. I can’t say for sure where we all stand as an art and culture sector, but I think there is a lot of questioning going on at the moment and that is not a bad thing. After all, something extremely big is happening to the entire cultural industry, so theatre can only come to deal with this».

Richard: «Yes, this situation forces you to ask questions about the nature of theatre itself, especially when you are dealing with Covid’s restrictions, such as the one that requires performers on stage to be one and half metres away from each other. Then you start asking yourself: what kind of theatre experience are we trying to get back into?

Now that we hear news about the vaccine, things have changed, because you can think that sooner or later the theatres will reopen without restrictions. But this situation is to be taken as an entirely positive challenge, because it invites us to ask ourselves complex questions that we would not have asked otherwise».

Claire: «On a political level, the British government is supporting artists: we personally are in a good position, the salary is reduced but we get it. Many people like freelancers, costume designers, light designers are not so well off, they fell through the safety net. For many people the situation is difficult, probably some will not be able to recover. Maybe the vaccine will put a brake on the situation, but I think we will carry the consequences of this period for a long time».

Richard: «Our company has been lucky, we have been in business for thirty-six years and this is what we do for a living, we are not in the same position as actors who are trying to get a job. However, I think the English administration is doing a good work, we have a lot to be grateful for, we are not starving».

Immagination

Richard: «In recent years we have worked a lot on the concept of theatre: in some cases we wanted to create very noisy and chaotic things, in which the eyes do not know where to position themselves – a pleasure of the theatre that the cinema is unable to reproduce; and where the spectator is called upon to constantly deal with what is in front of him. At other times, however, we have preferred to remove everything from the theatre: in the performance Dirty Work, two people talk about a show that has never been staged, telling only the beginning of the first act. The performance forces the audience to imagine the play. In Complete Works the spectator has to imagine that the objects have feelings and wishes, in order to understand when they are sad and when they are happy. Perhaps this is the heart of the storytelling: opening a tiny door for the imagination and asking the audience to fill in the details».

Claire: «In our work we are more interested in questions than answers. We have been thinking for a long time about what it means to tell a story, to tell a lie, to tell the truth; what it means to be a character, to pretend to be someone else. We like these things to be very complicated. In Complete Works the narration is centred around the subject of the story, and we actors remain in the background: when I play the part of Catherine in The Taming of the Shrew, it is not me, but her. In a way they are just fairy tales, from which you can take what you want».

Outro: To not disappear into darkness

Claire: «I think the spectators are very hungry, how else can you make sense of what’s happening? In what way can you describe it?»

Richard: «Complete Works – in the setting of the pandemic – is similar to Boccaccio’s Decameron: while the plague rages outside, inside the house we tell stories. This act allows us to take time to think, escape, and create spaces for discussion. Talking and reasoning about this moment – as we are doing now with you – is valuable. It helps everyone to not fall into loneliness, to not disappear into darkness».

L'autore

-

Giornalista e ricercatrice indipendente, scrive di cultura, teatro e attualità per testate online, riviste di settore e accademiche. È stata speaker e redattrice per Radiocittà Fujiko, ha co-curato un documentario radiofonico per RSI ed è audio-editor per radio e associazioni. Cura progetti di studio e divulgazione sull'audio fiction e sul rapporto tra teatro e podcast. Laureata in Dams e in Italianistica, si forma in giornalismo, radiofonia e podcasting attraverso workshop (Chora Academy, Centro di giornalismo permanente, Dinamo Press), masterclass (La Biennale di Venezia, Lucia Festival), corsi professionalizzanti (audio engineering base AFM Bologna).